Oldowan tools, consisting of stones with one to a few flakes removed, are the oldest widespread and temporally persistent hominin tools. The oldest of these were previously known from around 2.6 million years ago in Ethiopia, and by 2 million years ago, they were found to be quite widespread. Now, paleoanthropologists have discovered a new, older fossil site from around 3 to 2.6 million years ago in Kenya, where Oldowan tools were not only present, but were also being used to process a variety of foods, including hippopotamus and bovids. Thus, it appears that these tools were widespread much earlier than previous estimates and were widely used for food processing. Which hominins were using these tools remains uncertain, but Paranthropus fossils occur at the site.

Oldowan tools from the site of Nyayanga in Kenya: a dorsal flake, a ventral flake, and a core. Image credit: Plummer et al., doi: 10.1126/science.abo7452.

The appearance of Oldowan tools around 2.6 million years ago was a technological breakthrough that used systematically produced, sharp-edged flakes for cutting and cobbles or cores for percussion.

Although the Oldowan is often attributed to the genus Homo, multiple hominin species overlapped with these early tools, and it is possible that other genera, such as Paranthropus, made and/or used them.

Some scientists have linked emergent Oldowan technology to the first access to or more efficient processing of nutrient-rich animal carcasses.

Others have argued that plant food processing was the primary goal of early Oldowan stone tool usage, with increased carnivory — and butchery with stone tools) being added to the behavioral repertoire after 2 million years ago.

The evolutionary benefits connected with the emergence of Oldowan technology are unclear because of the paucity of Late Pliocene Oldowan sites, previously known only from the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia.

The new finds from the 3.03- to 2.6-million-year-old site at Nyayanga, Kenya, expand the geographic range of the earliest Oldowan tools by more than 1,300 km and the range of Paranthropus by approximately 230 km to southwestern Kenya.

“This is one of the oldest if not the oldest example of Oldowan technology,” said Queens College researcher Thomas Plummer, lead author of the study.

“This shows the toolkit was more widely distributed at an earlier date than people realized.”

Paranthropus boisei. Image credit: © Roman Yevseyev.

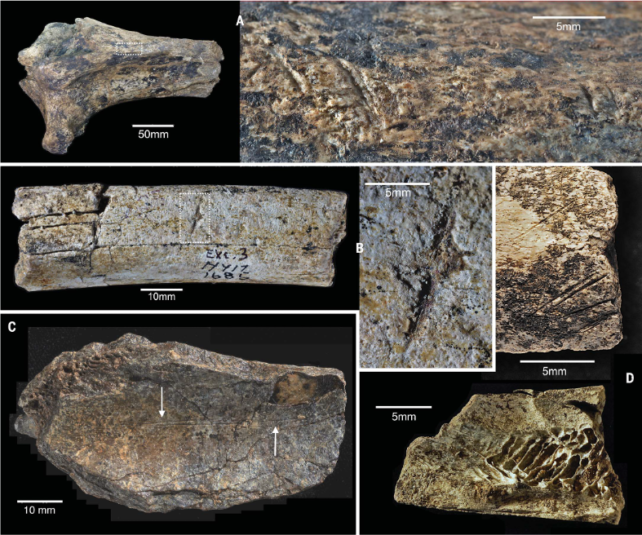

Not only were Oldowan tools present, but fossilized bones with associated stone-tool damage demonstrate the tools were used to butcher large animals: hippopotamids and bovids.

Furthermore, use-wear patterns on the tools themselves suggest the processing of plant materials.

“The site featured at least three individual hippos,” Dr. Plummer and colleagues said.

“Two of these incomplete skeletons included bones that showed signs of butchery.”

“We found a deep cut mark on one hippo’s rib fragment and a series of four short, parallel cuts on the shin bone of another.”

“We also found antelope bones that showed evidence of hominins slicing away flesh with stone flakes or of having been crushed by hammerstones to extract marrow.”

“The analysis of wear patterns on 30 of the stone tools found at the site showed that they had been used to cut, scrape and pound both animals and plants”

“Because fire would not be harnessed by hominins for another 2 million years or so, these stone toolmakers would have eaten everything raw, perhaps pounding the meat into something like a hippo tartare to make it easier to chew.”

The discovery of teeth from the muscular-jawed Paranthropus alongside these stone tools begs the question of whether it might have been that lineage rather than the Homo genus that was the architect of the earliest Oldowan stone tools, or perhaps even that multiple lineages were making these tools at roughly the same time.

“The behaviors preserved at Nyayanga are at least 600,000 years older than prior evidence of megafaunal carcass and plant processing and substantially predate the increase in absolute brain size documented in the genus Homo after 2 million years ago,” the authors concluded.

“The Late Pliocene expanded geography of the earliest Oldowan, and new evidence of its use in diverse tasks amplifies our understanding of the adaptive advantage of early stone technology in hominin diet and foraging ecology.”

Source: sci.news