Eating one’s own kind might be considered poor taste to us humans, but it’s a remarkably common survival tactic among other animals. Which is why we shouldn’t be surprised that dinosaurs also turned to cannibalism on occasion.

A haul of fossils from over 150 million years ago has provided palaeontologists with a rare glimpse into the chomping habits of Jurassic meat-eaters. Among the bones are signs that, in desperate times, one common theropod took desperate measures.

Theropod cannibals in a stressed Late Jurassic ecosystem. (Brian Engh)

Identifiable bite marks left by dinosaur diners are less common than most of us might imagine. The tooth imprints of theropods – avian dinosaurs, including Tyrannosaurus rex and velociraptors – have only been found in a few percent of bones in dinosaur fossil assemblages.

Unfortunately, this rarity makes it harder to come to definitive conclusions on which species left the marks. Most studies simply pin them on T. rex, perhaps thanks to its taste for bones, if not its general infamy.

The Mygatt-Moore Quarry in the US state of Colorado is something of an anomaly, however, revealing fossils with an unusually high density of cuts and impressions clearly made by theropod teeth.

Researchers from the University of Tennessee, Colorado Mesa University, and Daemen College in Amherst, New York took the opportunity of this bite-mark bounty to track down the genus most likely to be responsible.

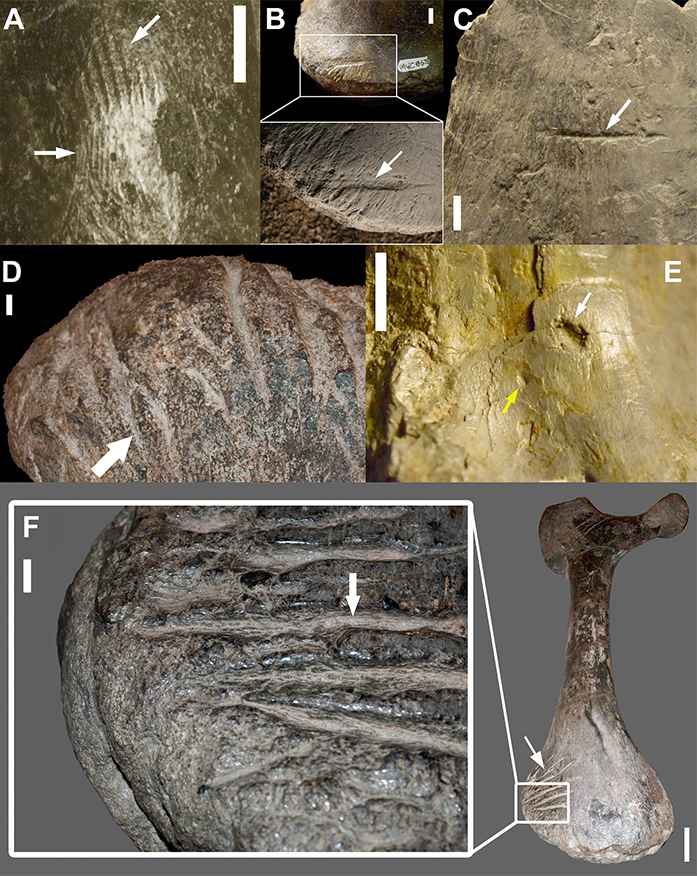

Pits, punctures, and cuts made by theropods on their own kind. (Drumheller et al., PLOS ONE, 2020)

Of the 2,368 bones lifted from the quarry so far (excluding a few out on display or on loan), just under one-third were chewed on by some kind of theropod.

On closer inspection, there were clues suggesting a heavyweight predator called Allosaurus was the guilty carnivore for at least a proportion of the cases.

At least one set of marks was large enough to be left by either an Allosaurus of remarkable size or another large dinosaur called Ceratosaurus. Similarly large predators, such as Saurophaganax and Torvosaurus, are also hard to rule out.

While most of the indentations were in bones of large herbivores, 17 percent of them were found on theropod bones, including other Allosaurs. Of those, about half were on parts of the skeleton unlikely to give a sizeable meal.

It’s not the first example of a dinosaur nibbling on its own brethren. Although rare, examples do pop up from time to time. This is, however, a first for this particular beast.

In desperate circumstances, it’s not hard to imagine a population of theropods turning on one another – or the remains of their dead – hungry for any nutrition they could find.

“Big theropods like Allosaurus probably weren’t particularly picky eaters, especially if their environments were already strapped for resources,” says University of Tennessee palaeontologist Stephanie Drumheller.

“Scavenging and even cannibalism were definitely on the table.”

The study is a fascinating example of dinosaur forensic dentistry being used to collect evidence on dinosaur behaviour, something palaeontologists rarely get a chance to study in so much depth.

Other features of the fossils, including the surrounding rock itself, might help explain why the bites were so numerous.

Signs point to long periods of exposure for the dead before they were covered in sediment. In lean times, perhaps, bodies scavenged from a graveyard of dying animals left out in the sun might have made for as good a lunch as any.

There is a chance that the way the fossils were brought together for storage accidentally concentrated the number of chomped bones, but the researchers suggest, even if this were the case, the site still stands out as a potential example of a stressful period in prehistory.

What feels like a gruesome and unsavoury practice is a behaviour many species of animal rely on, not just in desperation, but as a strategy for keeping up fitness while keeping down disease.

Finding examples of it among dinosaurs can tell us a great deal about how these magnificent beasts evolved to dominate the planet for so long.

Src: sciencealert.com