At only an inch long, the Hawaiian bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes) can be hard to spot in the warm, shallow waters off the Hawaiian Islands. During the day, this master of disguise buries itself in the sand on the seafloor, sometimes even gluing sand to its skin to hide. When the sun sets, the squid rises to hunt shrimp by the light of the moon and stars—and performs an even more impressive disappearing act. To prevent its moon shadow from sending a warning message to would-be prey, the bobtail squid relies on something called counter-illumination. The tiny hunter emits just enough light to match the moonlight shining down upon it, essentially erasing its shadow from the seafloor. (You can see the bobtail squid in animated action in the bioGraphic video, “Invisible Nature: The Glowing Squid.”)

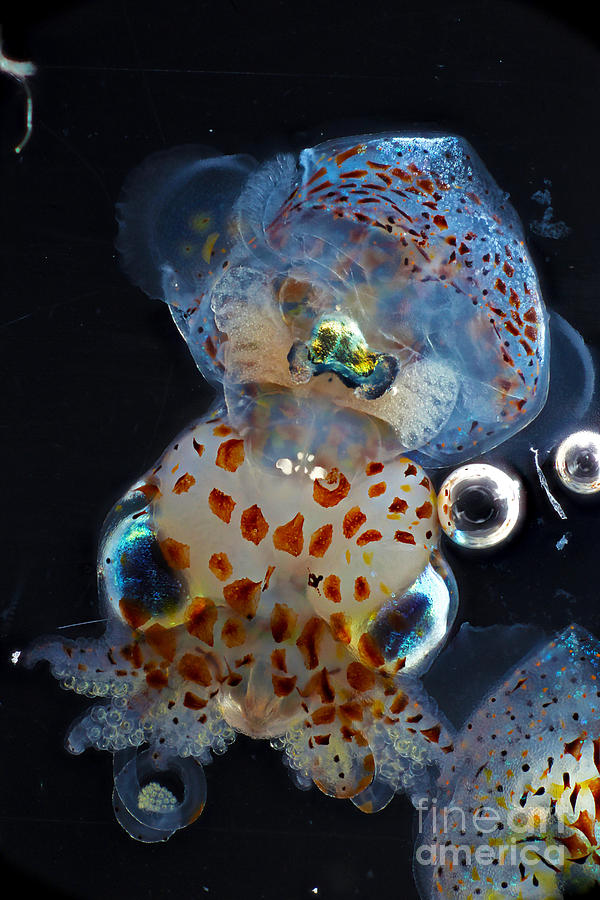

The squid can’t glow on its own, though. It relies on bioluminescent bacteria to fill its light organ—the black mass in this photo that resembles a tiny cowboy hat in the squid’s mantle. Although seawater is full of bacteria, the squid is looking for a single, rare species—Vibrio fischeri—that makes up about 0.1 percent of the bacteria in the ocean. The squid’s immune system keeps other species of bacteria at bay, but V. fischeri are ushered in and fed a steady diet of sugars and amino acids. Every night, these bacteria create the squid’s luminary disguise. (A squid can use its ink sac as a shutter to let more or less of the bacteria’s light through, depending on the fullness of the moon and the cloud cover in the sky.) And every morning, the squid flushes out its resident bacteria, replacing them with a new batch of V. fischeri over the course of the day.

Molecular and cell biologists at the University of Connecticut are trying to figure out how the squid’s immune system can recognize V. fischeri to allow it—and only it—into the squid’s light organ. They’re now getting an assist from photographer Mark R. Smith, whose photographs of the bobtail squid are so detailed that they reveal the animal’s internal organs. Using a technique called focus stacking, Smith takes multiple photos at different focal distances and digitally combines them, to create high-resolution photos that capture unprecedented color, depth, and detail. By zooming in on these photos, the researchers are able to see the development of embryonic squids, which begin to take on the bacteria the day they are born. The scientists’ ongoing efforts to understand how bobtail squid differentiate between good and bad bacteria may one day shed light on our own immune systems, which are often compromised by imbalances in our resident microbial communities.