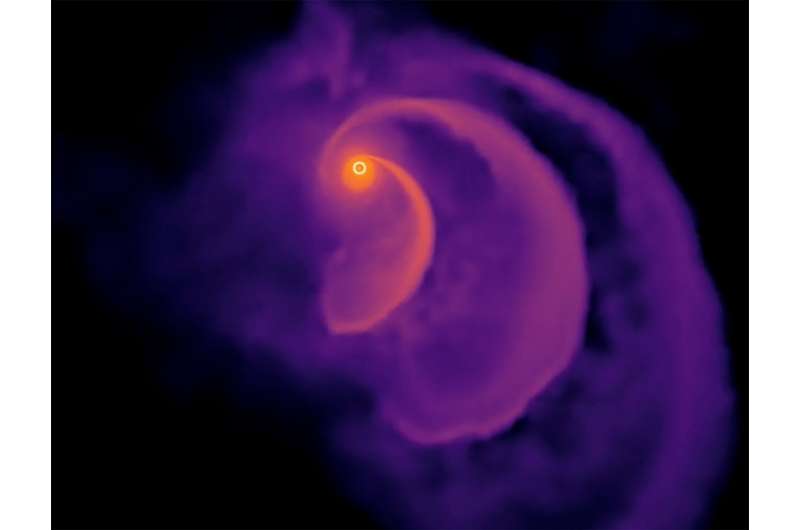

Remnants of a wayward star, circling around a black hole. Credit: Fulya Kıroğlu/Northwestern University

If they exist, intermediate-mass black holes likely devour wayward stars like a messy toddler—taking a few bites and then flinging the remains across the galaxy—a new Northwestern University-led study has found.

In new 3D computer simulations, astrophysicists modeled black holes of varying masses and then hurled stars (about the size of our sun) past them to see what might happen.

When a star approaches an intermediate-mass black hole, it initially gets caught in the black hole’s orbit, the researchers discovered. After that, the black hole begins its lengthy and violent meal. Every time the star makes a lap, the black hole takes a bite—further cannibalizing the star with each passage. Eventually, nothing is left but the star’s misshapen and incredibly dense core.

At that point, the black hole ejects the remains. The star’s remnant flies to safety across the galaxy.

Not only do these new simulations hint at the unknown behaviors of intermediate-mass black holes, they also provide astronomers with new clues to help finally pinpoint these hidden giants within our night sky.

“We obviously cannot observe black holes directly because they don’t emit light,” said Northwestern’s Fulya Kıroğlu, who led the study. “So, instead, we have to look at the interactions between black holes and their environments. We found that stars undergo multiple passages before being ejected. After each passage, they lose more mass, causing a flair of light as its ripped apart. Each flare is brighter than the last, creating a signature that might help astronomers find them.”

Kıroğlu will present this research during the virtual portion of the American Physical Society’s (APS) April meeting. The Astrophysical Journal has accepted the study for publication.

While astrophysicists have proven the existence of lower- and higher-mass block holes, intermediate-mass black holes have remained elusive. Created when supernovae collapse, stellar remnant black holes are about 3 to 10 times the mass of our sun. On the other end of the spectrum, supermassive black holes, which lurk in the centers of galaxies, are millions to billions times the mass of our sun.

Should they exist, intermediate-mass black holes would fit somewhere in the middle—10 to 10,000 times more massive than stellar remnant black holes but not nearly as massive as supermassive black holes. Although these intermediate-mass black holes theoretically should exist, astrophysicists have yet to find indisputable observational evidence.

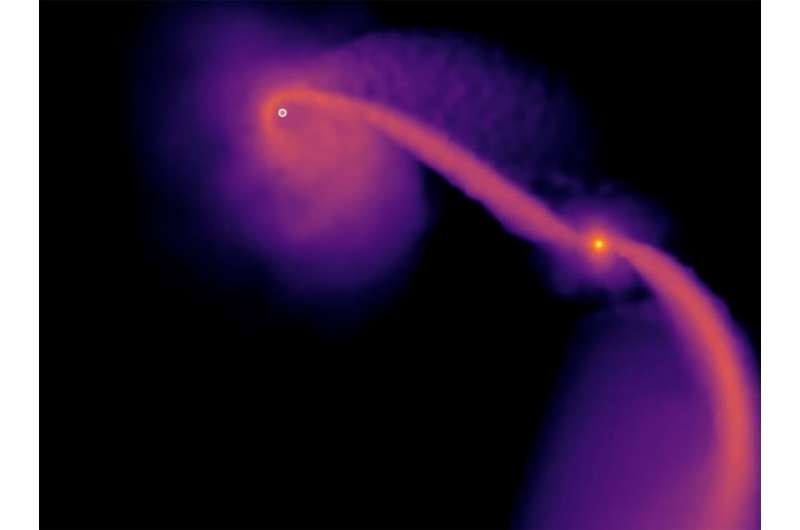

A star (bright orange dot on right) flying across the galaxy after being ejected from an intermediate-mass black hole (small ring on left). Credit: Fulya Kiroglu/Northwestern University

“Their presence is still debated,” Kıroğlu said. “Astrophysicists have uncovered evidence that they exist, but that evidence can often be explained by other mechanisms. For example, what appears to be an intermediate-mass black hole might actually be the accumulation of stellar-mass black holes.”

To explore the behavior of these evasive objects, Kıroğlu and her team developed new hydrodynamic simulations. First, they created a model of a star, consisting of many particles. Then, they sent the star toward the black hole and calculated the gravitational force acting on the particles during the star’s approach.

“We can calculate specifically which particle is bound to the star and which particle is disrupted (or no longer bound to the star),” Kıroğlu said.

Through these simulations, Kıroğlu and her team discovered that stars could orbit an intermediate-mass black hole as many as five times before finally being ejected. With each pass around the black hole, the star loses more and more of its mass as its ripped apart. Then, the black hole kicks the leftovers—moving at searing speeds—back out into the galaxy. The repeating pattern would create a stunning light show that should help astronomers recognize—and prove the existence of—intermediate-mass black holes.

“It’s amazing that the star isn’t fully ripped apart,” Kıroğlu said. “Some stars might get lucky and survive the event. The ejection speed is so high that these stars could be identified as hyper-velocity stars, which have been observed at the centers of galaxies.”

Next, Kıroğlu plans to simulate different types of stars, including giant stars and binary stars, to explore their interactions with black holes.