With giant palm trees stooping towards turquoise water, high-rise hotels glimmering in the sun, and opulent beachside restaurants selling lobster and expensive liqueurs, it’s easy to see why Maceio, the capital of Alagoas state, is known as Brazil’s Caribbean.

Yet like most cities in the country’s underdeveloped north east, this picture postcard scene tells only part of the story, the superficial face of a metropolis reliant on tourism. Venture a few blocks inland and a different Maceio gradually comes into view; the place regularly listed among Brazil’s most violent.

It is here, among the carpets of litter, filthy waterways and shanty housing, that a timid young boy with an ever-present smile started his journey from the streets to the Selecao, from Alagoas to Anfield.

Roberto Firmino Barbosa de Oliveira was born on 2 October 1991 in Trapiche da Barra, a poor neighbourhood squeezed between a polluted lake and a poverty-stricken favela. Inside his simple childhood home, he would drift off to the cacophony emanating from the nearby 20,000-capacity Estadio Rei Pele. It’s little wonder football was never far from his mind.

That home in Trapiche has recently been refurbished and converted into a hotdog store, but the Firmino family’s original rear wall remains. Its rusty metal anti-climb spikes are still there as well, still trusted to keep thieves out. They used to serve a second purpose too – keeping a determined young boy in.

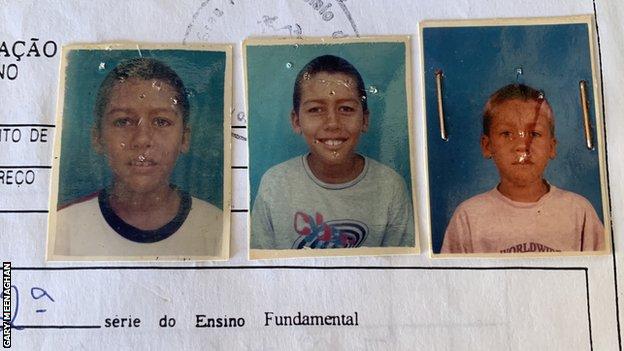

Childhood friend Bruno Barbosa dos Santos would play football against Firmino on his PlayStation 2. Firmino (pictured), who usually played as Corinthians, always won.

“It has always been violent here and Roberto’s mother was very protective of him,” says Bruno Barbosa dos Santos, a childhood friend of Firmino. “He was football mad, but it was difficult for him to be let out, so he would jump over the wall to come play with us in the street. One time he fell and had to get stitches in his knee. He still has the scar.”

Other friends recall how they would throw stones on to Firmino’s roof to tempt him out for a game, or how the coach at his first club Flamenguinho would set up a stepladder to make it easier for his star player to sneak away. Even when playing with children six years older, Firmino was a level above.

“Roberto’s mother worried that because of the neighbourhood he could become a bandit, but he never thought about that kind of thing,” says another old friend, Dedeu, who still lives in Trapiche.

“He was quiet and timid – he just smiled – but he was football crazy. Even when he didn’t have a ball, he’d be doing keepie-ups with an orange. His dream was to be a professional, but where we live it’s very difficult to achieve these things. That’s why I am so happy for him. He deserves all his success.”

Speak to anybody who knows Firmino or his parents Mariana Cicera and Jose Cordeiro and the sentiments are always the same. One particular Portuguese word comes up time and again: “humilde”. Humble. A dedicated family that earned its escape from poverty.

In order to evade his protective mother, Firmino would jump the back wall of his house. Sometimes, his coach would provide a stepladder to make life easier for his star player

Jose was a street vendor, selling bottled water from a coolbox outside music shows and football matches. It was the family’s only source of income and Roberto would help by collecting the money and giving change. But while dad fought to feed the family, son had a grander goal.

“He was always a good kid, thinking of others,” says Bruno, who remains in touch with the Liverpool forward, exchanging messages occasionally via WhatsApp. “Even now, he helped my grandmother; gave her a wheelchair after she had a stroke.

“His dream was to get his mother, father and sister out of here.”

Turn right at the top of Firmino’s childhood street, walk for a minute and you will reach a concrete five-a-side pitch lined with dirt and discarded waste. This is where Firmino honed his skills, practised his stepovers and improved his close control.

“He watched Ronaldinho Gaucho and Ronaldo on TV and wanted to be like them,” says Dedeu. “He would speak about Ronaldinho’s ability, but, man, he had it too. He was always much better than the rest. He was brilliant. He dribbled so well at times we’d end up on our asses.”

The small pitch sits at the entrance to the Escola Estadual Professor Tarcisio de Jesus, the school Firmino first attended aged seven. A sign on the headteacher’s door reads: “Start by doing what’s necessary; then do what’s possible; and suddenly you are doing the impossible.” Ari Santiago smiles as he reads it. A former administrative support agent, he is credited with starting the school football team, yet although he would urge his pupils to dream big, he never imagined one of his students would go on to play for Brazil.

Ari Santiago. The sign on the door reads: “Start by doing what’s necessary; then do what’s possible; and suddenly you are doing the impossible.”

“One of the things that made me create the team was that when I returned from vacation one year, I learnt that three students had been killed,” he recalls. “It was really violent here during that time and those deaths hurt me a lot. I thought: ‘Well, we are going to need to show these kids something other than this violence because if we don’t they’ll end up involved in it too.'”

The school team not only resulted in better behaviour among pupils worried they may be dropped, but it also gave Santiago reason to speak with a talented 14-year-old recognised as the best player in the school. Firmino had already signed youth papers for regional powerhouse Clube de Regatas Brasil (CRB) so could not play competitively for another team. He was, however, permitted to train and play in friendly matches.

“He was a very quiet boy, very calm, but always asking for a ball,” Santiago says. “I remember the balls were only available to the kids at certain times, but he would come and smile and make the sign of the ball with his hands. Sometimes I gave it, sometimes I didn’t. It was hard to say no to that smile.”

When the school was drawn against CRB in the quarter-finals of the local championship, Firmino cheekily advised his teacher to “bring a bag” to carry home all the goals he was going to score against him. Sure enough, he lived up to his promise, scoring in an 8-0 win. “The next day, I was in my office when he arrived,” recalls Santiago. “He passed by laughing but said nothing. Then he came back and gave a broader smile and left again. That was his way to express himself – through his smile.”

Firmino first attended the Escola Estadual Professor Tarcisio de Jesus aged seven and is remembered by his Religious Studies teacher, Gilvania Dias da Silva, as “a fun and smiley boy who was only ever interested in football”.

Earlier that year when Firmino attended his trial with CRB, his mother accompanied him, intrigued by neighbours’ belief that her son’s football skills could be the family’s ticket out of Trapiche. The club’s youth coach Guilherme Farias took only a few minutes to decide the gangly kid in the worn-out boots warranted a contract.

“What immediately caught my attention was the quality of his game,” says Farias, whose living room is filled with trophies and signed shirts of former players, including three-time Champions League winner Pepe. “Roberto was quiet, but the way he struck the ball was exceptional. I took him to the field and within three plays, I stopped him and said: ‘Get your papers ready, you’re coming to play for us.'”

Money was tight, but with the help of Farias and club dentist Marcellus Portella, Firmino travelled Brazil’s north east for two years playing junior championships as a deep-lying defensive midfielder, often in the same team as future Real Sociedad striker Willian Jose. At one point, he embarked on a 120-hour round trip by bus to Sao Paulo for a national tournament; his legs and feet swelling, but his enthusiasm never waning. “I have trained many talented boys,” says Farias, “but none who showed the same dedication as Roberto.”

Guilherme Farias coached Firmino for two years at CRB and said he always played cleanly, “unlike Pepe who was always very aggressive”. Farias has also worked with the likes of Willian Jose (Real Sociedad) and Otavio (Bordeaux).

Portella, who later became Firmino’s advisor and agent, adds: “Roberto was always positive and committed. I’ve never seen another player like him. I used to say: ‘One day, you’ll see this boy in the Brazil team.’ Everyone said this doctor is crazy, yet today there he is. I shut the mouths of a lot of people.”

Shortly after Firmino’s 16th birthday, Portella put CRB youth coach Toninho Almeida in contact with Luciano ‘Bilu’ Lopes, a midfielder from Alagoas who was winding up his career in Brazil’s south east. Almeida sent a highlights reel DVD of his prized possession and Bilu was impressed by Firmino’s dynamics “even on Maceio’s bad fields”. He helped organise a trial at Sao Paulo, the then-reigning top-flight champions, as well as his former club, Figueirense.

During two weeks in Sao Paulo, Firmino barely saw a ball and no offer arrived. He left frustrated yet unfazed, travelling south to Santa Catarina state. This time, despite uncertainty among the Figueirense coaches because of his quietness, when a ball appeared, he let his feet do his talking.

“Roberto arrived for a trial in the middle of 2008,” recalls Hemerson Maria, who was coach of Figueirense Under-17s. “Generally trials last a maximum of one month, but depending on the player it can be less: two weeks, 10 days, etc.

“Roberto’s trial lasted only 30 minutes – he was exceptional. He practically did nothing wrong, showed immense technical quality, and to top it off scored two bicycle kicks. Afterwards, everyone was talking about him and I realised we had a very special player on our hands.”

Maria immediately changed Firmino’s position on the field, moving him closer to the attack. Homesick but hell-bent on making the most of his opportunity, the young hopeful would keep in touch with friends back in Maceio via social networking website Orkut and MSN Messenger, telling them he only intended to return once he was successful. His timidity though remained a concern. Maria called him ‘Alberto’ for two weeks without being corrected.

Bilu, who would go on to be best man at Firmino’s wedding, recalls: “Soon after I took Roberto to Figueirense, I got a call from the base coordinator asking if he was mute, because he was so quiet. I called him and said: ‘Roberto, you have to speak, ask for the ball, talk to the staff.’ He didn’t say anything, he just laughed.”

Yet while his voice was quiet, the noise surrounding him was growing. In 2009, before he had even played for the Figueirense first team, he was invited for a trial at Marseille. But his journey to the south of France involved a stopover in Spain and things quickly went awry. Despite the fact Firmino was only changing flights, immigration at Madrid-Barajas Airport accused him of trying to enter the country without prerequisite paperwork and he was deported in tears.

Arriving back in Brazil, Firmino was met by Maria who lifted the 17-year-old’s spirits by reminding him Cafu had experienced similar disappointments early in his career before captaining Brazil to World Cup glory. A month later, he made the trip to Marseille again – this time on a direct flight – but ultimately the French club decided against paying his 1m euro (£860,000) release clause. “Given what he’s achieved since, it has to go down as an error on our part,” Jean-Philippe Durand, Marseille’s former personnel chief, admitted in 2018.

Firmino poses with former classmate and Flamenguinho teammate Lucialdo da Silva Almeida during a visit to Trapiche in 2018 when he donated 500 food baskets, snacks and toys for the schoolchildren.

Three weeks after Firmino’s 18th birthday, he made his professional debut dressed in the baggy black and white stripes of Figueirense and wearing number 16. Thirteen months later, he was named Serie B’s Most Promising Player having helped his club win promotion to the top flight. By the end of December 2010, despite attracting scouts from Arsenal and PSV Eindhoven, he signed for Hoffenheim for 4m euro (£3.4m).

Swapping the sunshine of Santa Catarina for the snow of south-west Germany was a challenge, but as his coaches always said, Firmino’s dedication sets him apart. After a couple of years acclimatising, he was voted the Bundesliga’s Breakthrough Player of the Season. By the time Liverpool beat off competition from Manchester United and Manchester City to sign him for £29m in July 2015, he was a full Brazil international. “His departure left us with one eye laughing and the other shedding a tear,” Hoffenheim’s director of football Alexander Rosen told World Soccer in 2018.

Since then, Firmino’s career trajectory has only steepened. In the past 12 months, he has won the Champions League, the Copa America, and is set to lift the Premier League trophy this season. In August, he became the first Brazilian to score 50 goals in the English top flight and in December scored the only goal as Liverpool beat South American champions Flamengo in the final of the Club World Cup.

Yet the boy who benefited from others’ generosity in his early years has never forgotten his roots. In July 2018, shortly after becoming only the third male from Alagoas to play at a World Cup, he returned to his former school in Trapiche, taking with him 500 food hampers for local families, as well as toys and a trampoline for the children. Be it donating £60,000 to pay a family’s medical bills, making monthly financial contributions to a hospital in Santa Catarina, or buying a round of drinks for 200 strangers at one of his favourite Maceio restaurants, at times it seems everybody who knows him has a story to tell of his big-heartedness.

Nevertheless there remains a feeling Firmino is not fully appreciated in his homeland. Perhaps, say his friends and former coaches, it is because he never played for one of the traditional powerhouses in Sao Paulo or Rio de Janeiro. Even at the Museum of Sports at Estadio Rei Pele, among the bronze busts of Alagoan heroes Mario Zagallo and Dida, there is nothing to commemorate the superstar who was, literally, born just down the road.

Predictably, such sentiment does not extend to the streets of Maceio. Here, be it among the giant palms and high-rise hotels or the pollution and plastic waste, Firmino remains their humble, unheralded hero. Sergio Araujo, a mobile phone technician relaxing near Ponta Verde beach, puts it best.

“Roberto is the best Brazilian player in the world right now,” he says. “He would never say it, but I will: Neymar is not fit to lace his boots.”