NASA recently announced the discovery of a new, Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone of a nearby star called TOI-700. We are two of the astronomers who led the discovery of this planet, called TOI-700 e. TOI-700 e is just over 100 light years from Earth – too far away for humans to visit – but we do know that it is similar in size to the Earth, likely rocky in composition and could potentially support life.

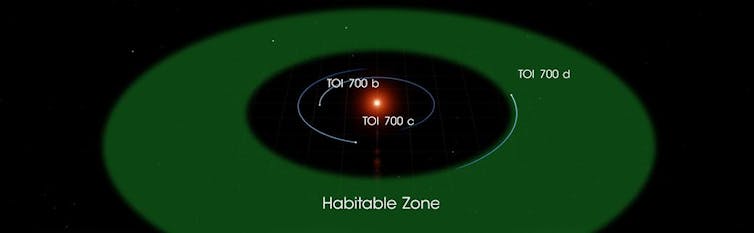

The TOI-700 star system is home to four planets, including two in its habitable zone that could host liquid water. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

You’ve probably heard about some of the many other exoplanet discoveries in recent years. In fact, TOI-700 e is one of two potentially habitable planets just in the TOI-700 star system.

Habitable planets are those that are just the right distance from their star to have a surface temperature that could sustain liquid water. While it is always exciting to find a new, potentially habitable planet far from Earth, the focus of exoplanet research is shifting away from simply discovering more planets. Instead, researchers are focusing their efforts on finding and studying systems most likely to answer key questions about how planets form, how they evolve, and whether life might exist in the universe. TOI-700 e stands out from many of these other planet discoveries because it is well suited for future studies that could help answer big question about the conditions for life outside the solar system.

From 1 to 5,000

Astronomers discovered the first exoplanet around a Sun-like star in 1995. The field of exoplanet discovery and research has been rapidly evolving ever since.

At first, astronomers were finding only a few exoplanets each year, but the combination of new cutting-edge facilities focused on exoplanet science with improved detection sensitivity have led to astronomers’ discovering hundreds of exoplanets each year. As detection methods and tools have improved, the amount of information scientists can learn about these planets has increased. In 30 years, scientists have gone from barely being able to detect exoplanets to characterizing key chemical clues in their atmospheres, like water, using facilities like the James Webb Space Telescope.

Today, there are more than 5,000 known exoplanets, ranging from gas giants to small rocky worlds. And perhaps most excitingly, astronomers have now found about a dozen exoplanets that are likely rocky and orbiting within the habitable zones of their respective stars.

Astronomers have even discovered a few systems – like TOI-700 – that have more than one planet orbiting in the habitable zone of their star. We call these keystone systems.

The TOI-700 system has a large habitable zone, and the newly discovered TOI-700 e, not shown in this image, orbits the star along the inner edge of the habitable zone. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

A pair of habitable siblings

TOI-700 first made headlines when our team announced the discovery of three small planets orbiting the star in early 2020. Using a combination of observations from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Surveying Satellite mission and the Spitzer Space Telescope we discovered these planets by measuring small dips in the amount of light coming from TOI-700. These dips in light are caused by planets passing in front of the small, cool, red dwarf star at the center of the system.

By taking precise measurements of the changes in light, we were able to determine that at least three small planets are in the TOI-700 system, with hints of a possible fourth. We could also determine that the third planet from the star, TOI-700 d, orbits within its star’s habitable zone, where the temperature of the planet’s surface could allow for liquid water.

The Transiting Exoplanet Surveying Satellite observed TOI-700 for another year, from July 2020 through May 2021, and using these observations our team found the fourth planet, TOI-700 e. TOI-700 e is 95% the size of the Earth and, much to our surprise, orbits on the inner edge of the star’s habitable zone, between planets c and d. Our discovery of this planet makes TOI-700 one of only a few known systems with two Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zone of their star. The fact that it is relatively close to Earth also makes it one of the most accessible systems in terms of future characterization.

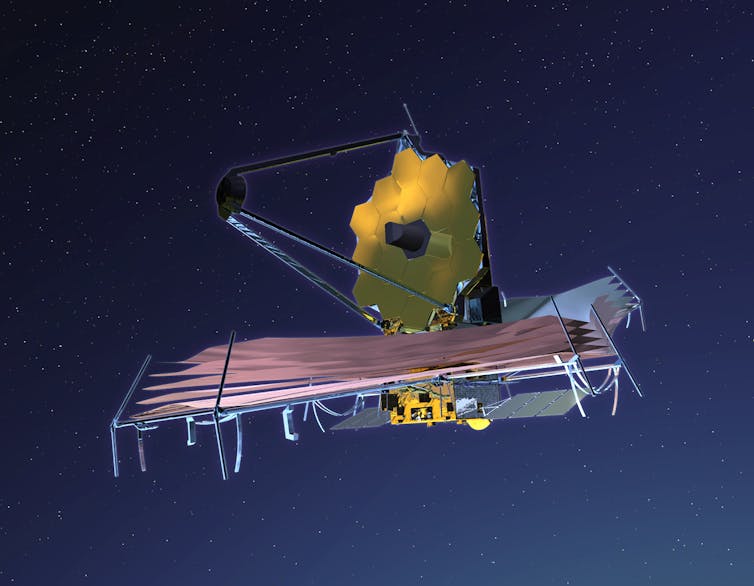

New tools, like the James Webb Space Telescope, can provide clues about life on distant planets, but with thousands of scientific questions to answer, efficient use of time is key. Bricktop/Wikimedia Commons

The bigger questions and tools to answer them

With the successful launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers are now able to start characterizing the atmospheric chemistry of exoplanets and search for clues about whether life exists on them. In the near future, a number of massive, ground-based telescopes will also help reveal further details about the composition of planets far from the solar system.

But even with powerful new telescopes, collecting enough light to learn these details requires pointing the telescope at a system for a long period of time. With thousands of valuable scientific questions to answer, astronomers need to know where to look. And that is the goal of our team, to find the most interesting and promising exoplanets to study with the Webb telescope and future facilities.

Earth is currently the only data point in the search for life. It is possible alien life could be vastly different from life as we know it, but for now, places similar to the home of humanity with liquid water on the surface offer a good starting point. We believe that keystone systems with multiple planets that are likely candidates for hosting life – like TOI-700 – offer the best use of observation time. By further studying TOI-700, our team will be able to learn more about what makes a planet habitable, how rocky planets similar to Earth form and evolve, and the mechanisms that shaped the solar system. The more astronomers know about how star systems like TOI-700 and our own solar system work, the better the chances of detecting life out in the cosmos.

source: theconversation.com