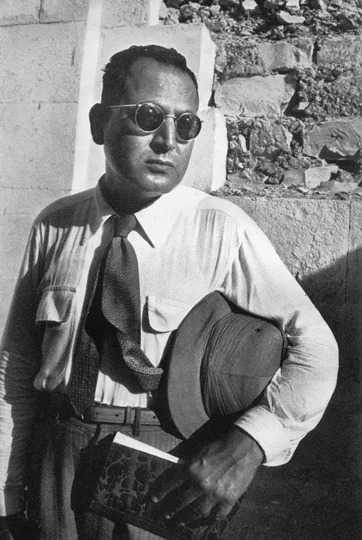

Egypt’s ancient past is littered with a plethora of unexplained finds. In the mid-1950s, archaeologist Zakaria Goneim uncovered one such find. Gone’s discovery was so unusual that academics debated what the archaeologist discovered and why it was important.

Archaeologist Zakaria Ghoneim discovered a wall in 1951 while looking for fresh, unspoiled remains. He believes it might be one of the unknown, incomplete ancient pyramids. The structure’s ruins were discovered in Saqqara’s cemetery, not far from Djoser’s ancient step pyramid, which is said to be 4,700 years old.

“It may be supposed that, since the building had been utilized as a quarry in later times, its presence was known until a fairly recent date,” Goneim wrote in his book “The Lost Pyramid” (Rinehart & Company, 1956). Fortunately, I could ascertain that the monument had been unaltered for at least 3,000 years, if not more. My workers discovered many later burials during the excavations, the earliest of which dated from the Nineteenth Dynasty (1349-1197 B.C. ). And some of which were found lying undisturbed above the buried pyramid itself proved that human eyes had not seen the walls we had uncovered since that distant epoch.”

Finding the entrance to the unfinished pyramid was a question of technique because the Egyptian pyramids’ doors are positioned in the center of the northern side.

Gone began his quest for the pyramid entrance in January 1954, believing that “no superstructure would have been created without the substructure being completed first.” He discovered the remnants of a funerary temple while excavating the northern side. Encouraged, he went looking for the entrance there, as the opening of Djoser’s pyramid was also located there. When it failed, he relocated the project to the north. Finally, he discovered what looked to be the entry gallery approximately 75 feet from the pyramid face.

Heavy stones were thrown into the gallery at random intervals, and the spaces were filled with debris. The gateway to the pyramid was eventually discovered. “We discovered the entryway was intact, sealed with stone,” Goneim recalled, “to our immense relief.” On March 9, 1954, the pyramid was inaugurated.

The entrance led to a lofty gallery dug into the bedrock, but they were met with a rubble wall stretching from floor to ceiling after only sixty feet. The researchers discovered a vertical tunnel in the top through which the rubble had been thrown. The shaft’s mouth was buried in the pyramid superstructure above.

Since the pyramid’s construction, Goneim concluded that the shaft had not been breached. The rubble obstruction in the corridor was almost fifteen feet deep, but first, the post had to be cleaned so that the material didn’t fall on the employees below. A catastrophe happened while cleaning the shaft, which caused the excavation to be halted for a considerable period. One of the stone blocks crashed, burying the workers and killing one of them. This sparked rumors of a pyramid curse, and the story has amplified the story, which said the pyramid had collapsed and killed 80 people.

Then word got around that a terrible ghost was imprisoned in the tomb, ready to kill everyone. Gone was terrified as well, but he persisted in digging. He was gone discovered several burial containers after clearing the room. On the seals, he read the name of a “hitherto unknown ruler,” Sekhemkhet (another word, Djoser Tati, had known this pharaoh).

They were gone and discovered a golden treasure, including 21 golden bracelets, wrist hoops, tweezers, a sickle-shaped golden wand, golden plates, a golden shell-powder box, and several carnelian beads.

They had to make their way to the room via earthquake-damaged stone shards obstructing the tunnel. They discovered a side entrance at 31 meters that led to a lengthy T-shaped corridor with 120 vacant storage chambers. The archaeologist found a burial room buried beneath defensive masonry and massive stone blocks after another 72 meters. It was located in the heart of Sekhemkhet’s unfinished pyramid.

“A gorgeous sarcophagus of pale, golden, translucent alabaster rested in the center of a rough-cut room.” We moved closer to it. “Is it intact?” was my initial thinking. I hurriedly searched the top for the lid with my electric flashlight. But there was no lid; the top and the rest were made of the same material,” Goneim wrote.

Archaeologists unearthed various unusual objects after cleansing them of sand and dust. A type of funeral wreath was placed on the tomb in the shape of the letter V. Second, one of the corners had meticulously repaired chips. Finally, the sarcophagus lid was not at the top but the bottom and went up, and the archaeologists were standing in front of a trap for a wild animal rather.

The cement used to spread the lid was in good condition. Archaeologists created a space around the coffin, set lifting blocks, and opened the “coffin” with much effort, convinced that Sekhemkhet’s body was within. It was completely vacant on the inside. Gone’s dissatisfaction was unfathomable. Due to the heat, the excavation season normally ends around April. As a result, the expedition toiled until June 26 amid the heat and stuffiness. And that was all for the sake of discovering an empty coffin! The excavations were brought to a halt.

When Ghoneim returned to work in 1955, he cleaned the gallery and discovered several items, but he could not answer the pyramid’s puzzle. Is it possible that an evil spirit was imprisoned in the coffin? Gone succumbed to the curse soon after, and in 1959, he drowned himself in the Nile.

The pyramid’s age was calculated by Goneim himself to be 4700 years old. According to a radiocarbon examination, the “wreath” atop the coffin was 800 years older than the pyramid. Why did the Egyptians abandon the pyramid’s construction, and why did they decide to leave? Why were the tunnels so meticulously built and the coffin so meticulously closed? What was the purpose of putting ancient dried plants on it? There are a few different variations of this.

Experts are still baffled by the pyramids’ interior construction. Only a snake can navigate the numerous small, sloped, vertical tunnels. In addition, the Egyptian deity Nehebkau, the judge of the dead, could transform into a serpent. The app is an ancient Egyptian demon of evil, darkness, and destruction that takes the appearance of a gigantic snake and is the sun god Ra’s arch-nemesis.

Jean-Philippe Lauer began excavating Sekhemkhet’s monument in 1963 by looking into the potential of a south tomb, which he had discovered on the southern side of Djoser’s Step Pyramid. He also sought to piece together a plan of the Buried Pyramid and figure out what had happened to the missing mummy.

Under a ruined mastaba, Lauer discovered the foundations of the south tomb. He found the remnants of an early wooden coffin in a hallway at the bottom of a deep hole, which included the bones of a two-year-old kid (a royal prince?) together with several Dynasty III utensils and gold leaf shards. Robbers had taken advantage of the burial room. Lauer proved gone’s idea that the complex’s enclosing wall had been enlarged. The Buried pyramid’s incompleteness has sparked many ideas that remain unsolved.