Paleontologists have examined the fossilized brain and cranial nerve soft tissues of Coccocephalus wildi, a species of early ray-finned fish that lived 319 million years ago.

Life reconstruction of Coccocephalus wildi. Image credit: Márcio L. Castro.

Coccocephalus wildi lived in what is now England during the Carboniferous period, some 319 million years ago.

The species was 15 to 20 cm (6-8 inches) long, about the size of a bluegill, and was probably a carnivore.

It likely inhabited an estuary and dined on small crustaceans, aquatic insects and cephalopods, a group that today includes squid, octopuses and cuttlefish.

First described in 1925, its type and only specimen was recovered from the roof of the Mountain Fourfoot coal mine in Lancashire. The fossil was found in a layer of soapstone adjacent to a coal seam in the mine.

Soft tissues such as the brain normally decay quickly and very rarely fossilize. But when this individual of Coccocephalus wildi died, the soft tissues of its brain and cranial nerves were replaced during the fossilization process with a dense mineral that preserved, in exquisite detail, their three-dimensional structure.

“An important conclusion is that these kinds of soft parts can be preserved, and they may be preserved in fossils that we’ve had for a long time — this is a fossil that’s been known for over 100 years,” said Dr. Matt Friedman, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan.

“This unexpected find of a three-dimensionally preserved vertebrate brain gives us a startling insight into the neural anatomy of ray-finned fish,” said Dr. Sam Giles, a paleontologist at the University of Birmingham.

“It tells us a more complicated pattern of brain evolution than suggested by living species alone, allowing us to better define how and when present day bony fishes evolved.”

“Comparisons to living fishes showed that the brain of Coccocephalus wildi is most similar to the brains of sturgeons and paddlefish, which are often called ‘primitive’ fishes because they diverged from all other living ray-finned fishes more than 300 million years ago.”

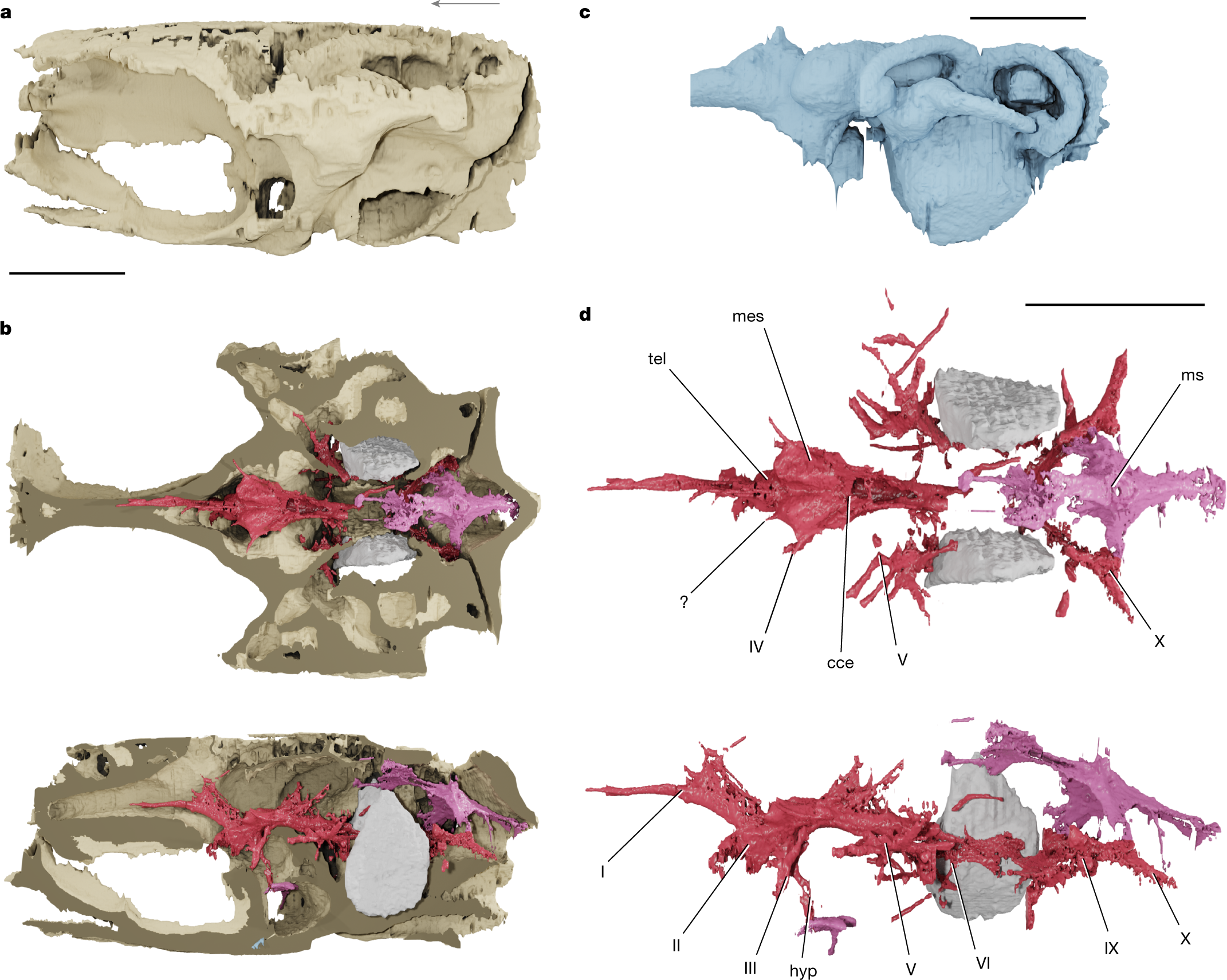

The fossilized skull of Coccocephalus wildi. Image credit: Jeremy Marble, University of Michigan.

Paleontologists were not looking for a brain when they examined the skull fossil for the first time, but discovered an unusual, distinct object inside the skull.

The object displayed several features found in vertebrate brains: it was bilaterally symmetrical, it contained hollow spaces similar in appearance to ventricles, and it had multiple filaments extending toward openings in the braincase, similar in appearance to cranial nerves, which travel through such canals in living species.

Significantly, the brain of Coccocephalus wildi folds inward, unlike in all living ray-finned fishes, in which the brain folds outward.

“Not only does this superficially unimpressive and small fossil show us the oldest example of a fossilized vertebrate brain, but it also shows that much of what we thought about brain evolution from living species alone will need reworking,” said Dr. Rodrigo Figueroa, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan.

Source: sci.news